“Whatever the case,” we learn in “Scheherazade,” “Scheherazade had a gift for telling stories that touched the heart.” This story’s man is a shut-in, although why is never revealed, and the woman offers him awkwardly satisfying sex and, as noted above, stories. Someone new to Murakami may find the men too flawed to deserve the compassion Murakami seems eager to solicit.Īs a Murakami fan and literary scholar of his work, I think the collection shines most powerfully with “Scheherazade” and “Samsa in Love”-both of which center loneliness in ways that rise above the more problematic portrayals of men and women.

The lonely, abandoned man is a staple of Murakami-and the stories include many signature elements of his fiction, such as The Beatles, quirky narration and the centering of storytelling, bar tending and jazz, and the ever-present hint of the supernatural, the unexplainable.įor readers already drawn to Murakami, this collection reaches out to them while often remaining subtle and nearly stationary.

It was that hand that had caressed my wife’s naked body, he thought. After Takatsuki had walked off into the drizzle in his beige raincoat, Kafuku, as was his habit, looked down at his right palm. Kafuku begins a friendship with one of his wife’s lovers after her death, in fact: Throughout the collection, Murakami paints these men sympathetically despite their many flaws. As far as he knew, there had been four such affairs. His wife, however, slept with other men on occasion. The urge had never arisen, although he had received his fair share of opportunities. He hadn’t slept with another woman in all the years of marriage. He had fallen deeply in love with her when they first met (he was twenty-nine), and this feeling had remained unchanged until the day she died (he had been forty-nine then). Murakami, however, investigates loneliness through the lens of men such as Kafuku: The shallowness of men, the weaknesses of men who embody and perpetuate sexism and misogyny-these would seem to be the sorts of fictional investigations needed in the twenty-first century. Kafuku, an aging actor, hires a woman, Misaki Watari, to be his driver-a sparse plot common in Murakami, whose work is often driven by characters and narration instead of traditional action.

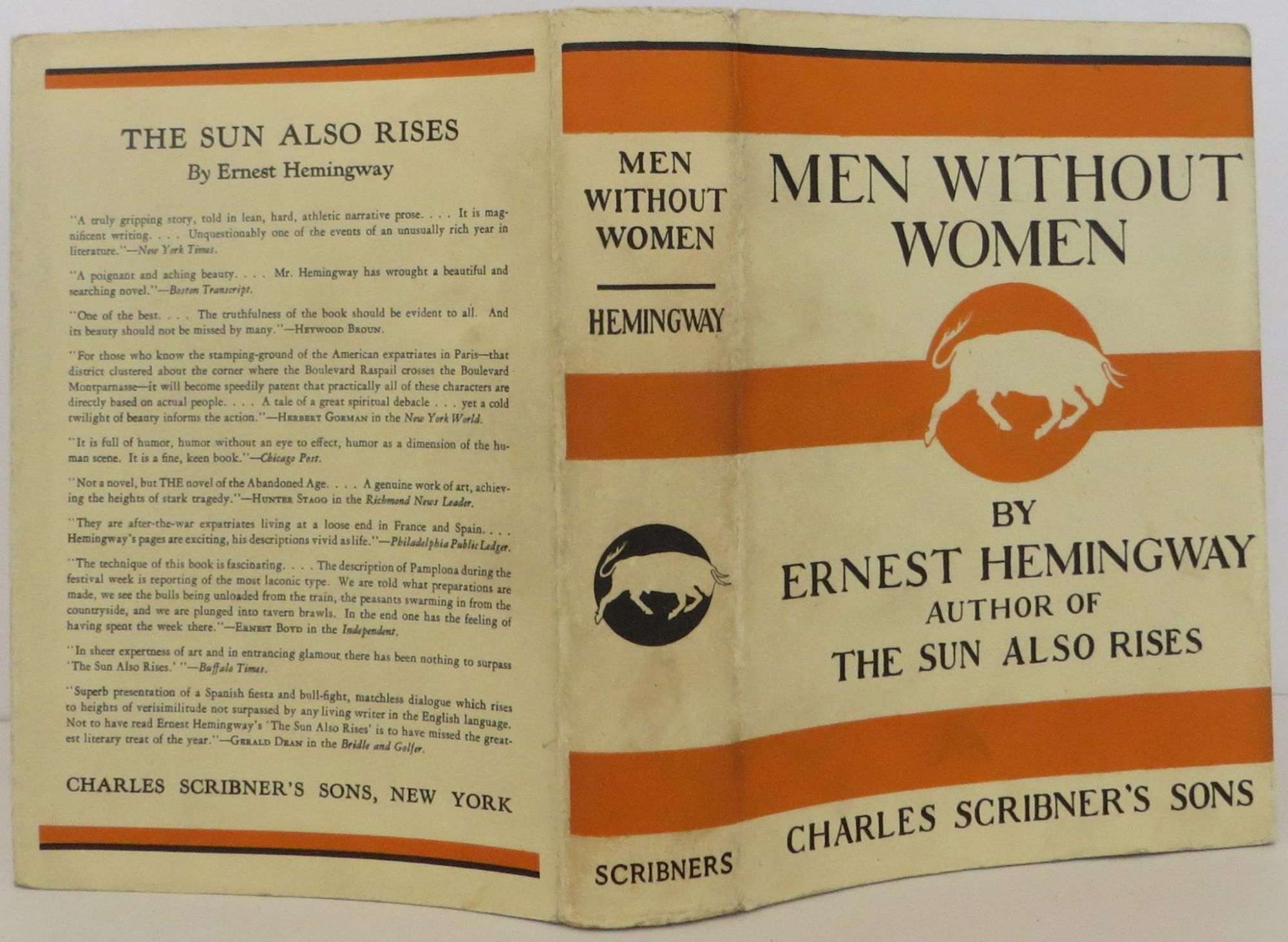

“Drive My Car” opens Murakami’s slim collection by immediately challenging reader’s with “most female drivers fell into one of two categories,” leading into a story uncritically awash in sexism. Could we possibly need yet another fictional investigation of men in 2017? Haruki Murakami’s Men Without Women suggests we do with seven short stories that blend a narrative focus on men who seem equally inept at connecting with women and ultimately incomplete when women seem destined to leave, to be absent.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)